I am about to put together a presentation on oral language so my next few blogs will explore the research that supports this area. There are many aspects to oral language and I have already explored Konza’s work on oral language as part of the Big 6.

This blog will consider the importance of oral rehearsal, something that Lyn Sharratt (author of Putting faces on the data) paid a lot of attention to in her recent work with Metropolitan schools in Brisbane, Queensland.

It is interesting when you google ‘oral rehearsal’ – there isn’t much about it. Yet, oral rehearsal in writing is a necessary prerequisite for thoughtful writing pieces (Sharratt & Fullan, 2012).

Not only is it necessary for writing, but any speaker should be given opportunity to rehearse before sharing their thoughts in a public forum. This includes teachers in staff meetings and professional development and of course, students before they have to share orally in the classroom.

This makes sense – how many of us ‘rehearse’ what we are going to say prior to a formalised presentation. One of the reasons I sometimes avoid contributing in a public forum, is because I haven’t had the opportunity to rehearse what I would like to say. If I feel like this, how do some of my students feel?

Calkins (2001) stated that, ‘In schools, talk is sometimes valued and sometimes avoided….and this is surprising – talk is rarely taught…Yet talk, like reading and writing, is a major motor – I could even say the major motor – of intellectual development’ (p.226).

A search in the United Kingdom of the term, Oral Rehearsal, undertaken by the Department for Children, Schools and Families found ten references:

- Using writing partners and oral rehearsal,

- After oral rehearsal, write explanatory texts independently from a flowchart or other diagrammatic plan, using the conventions modelled in shared writing.

- Rehearse sentences orally before writing and cumulatively reread while writing

- The trainer repeatedly models rehearsal of sentences in speech before committing them to paper…

- The importance of oral rehearsal and cumulative re-reading

- Oral rehearsal before writing

- Rehearse sentences orally before writing and cumulatively reread while writing

- A range of drama and speaking and listening activities that support appropriate oral rehearsal prior to the written outcomes.

- Oral rehearsal prior to writing…. In pairs, children rehearse phrases and sentences, using some of the ideas suggested.

- Scribe the sentence, modelling its oral rehearsal before you write it.

- Oral rehearsal: in particular, those children who have poor literacy skills; for children with poor language skills.

All of these refer to rehearsing orally prior to writing. I would go further and promote oral rehearsal before speaking informally and formally.

A study by Myhill and Jones noted that a teacher employing oral rehearsal practice in her classroom observed improvement in the use of imaginative written text and in low-attaining writers. She attributed improvement in her student’s writing to the fact that oral rehearsal allowed the children ‘to think about before writing it down’ and that oral rehearsal made it ‘easier to change it [writing] in talk than when it had been written down.

Give students the opportunity to talk things out prior to speaking publicly or to written responses!

Give students the opportunity to talk things out prior to speaking publicly or to written responses!

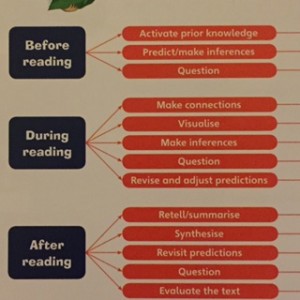

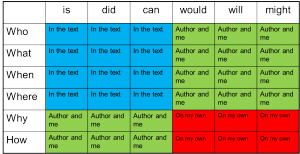

Teacher think aloud: “As I read the text, I picture what is happening here. I think about the text more deeply, generate (make up) questions, and formulate (work out) answers to my questions.”

Teacher think aloud: “As I read the text, I picture what is happening here. I think about the text more deeply, generate (make up) questions, and formulate (work out) answers to my questions.”

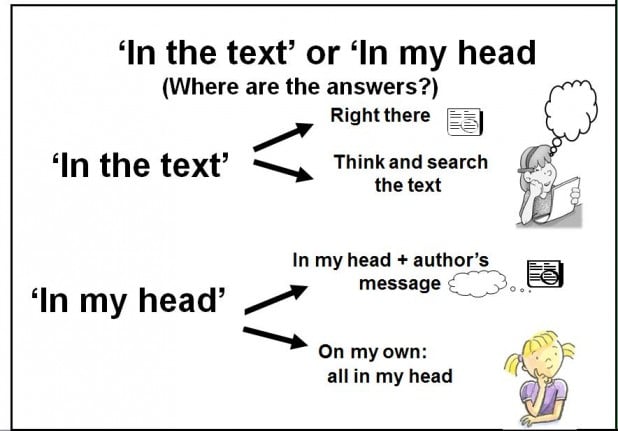

In my last blog, I looked at Konza’s sixth component of teaching reading: comprehension. Konza mentioned the importance of questioning as a comprehension strategy. One of the questioning frameworks that I have used quite successfully is Blank’s levels of questions.

In my last blog, I looked at Konza’s sixth component of teaching reading: comprehension. Konza mentioned the importance of questioning as a comprehension strategy. One of the questioning frameworks that I have used quite successfully is Blank’s levels of questions.

Comprehension is not just finding answers in a piece of text – it is an active process whereby the reader creates a version of the text in his or her mind (Konza, 2011).

Comprehension is not just finding answers in a piece of text – it is an active process whereby the reader creates a version of the text in his or her mind (Konza, 2011).

Fluency is the ability to read text accurately, quickly and with expression. Background knowledge of the text being read, rapid retrieval of relevant vocabulary and knowledge of syntax and grammatical forms assist students to predict upcoming vocabulary with accuracy and speed.

Fluency is the ability to read text accurately, quickly and with expression. Background knowledge of the text being read, rapid retrieval of relevant vocabulary and knowledge of syntax and grammatical forms assist students to predict upcoming vocabulary with accuracy and speed. These include:

These include: