Before I move onto the next component in Konza’s Big 6, I thought I would draw attention to Misty Adoniou’s paper, ‘Seven things to consider before you buy into phonics programs’. This is a reminder that although explicitly teaching phonics is necessary for many students, it is only one component of a balanced reading approach.

Before I move onto the next component in Konza’s Big 6, I thought I would draw attention to Misty Adoniou’s paper, ‘Seven things to consider before you buy into phonics programs’. This is a reminder that although explicitly teaching phonics is necessary for many students, it is only one component of a balanced reading approach.

Image from: Wayan Vota via Compfight cc

If you have had a chance to explore Version 8 of the Australian Curriculum English, you would have noticed a greater emphasis on phonics in the earlier years, and that from year 3 onwards, it states that phonological and phonemic awareness will continued to be applied when connecting spoken and written language. Below is Adoniou’s paper, which I found to be an interesting read.

Seven things to consider before you buy into phonics programs

Misty Adoniou, University of Canberra

Phonics, or teaching reading, writing and spelling through sounds, is often touted as the golden path to reading and writing.

National curricula in England and Australia have been rejigged to increase their focus on phonics, and entrepreneurs and publishers have rushed to fill the space with phonics programs and resources.

But before you buy their wares, consider the following.

1. English is not a phonetic language

This may be an inconvenient truth for those promoting phonics programs, but English is not a phonetic language and never has been.

English began about 1500 years ago as a trio of Germanic dialects brought over to the islands we now know as the British Isles. Latin speaking missionaries arrived soon after to convert the pagans to Christianity. They also began to write the local lingo down, using their Latin alphabet.

The Latin alphabet was a good phonetic match for spoken Latin, but it was not a good match for spoken Old English.

There were sounds in Old English that simply didn’t exist in spoken Latin, so there were no Latin letters for them. And there were sounds in Latin that didn’t exist in Old English, which left some Latin letters languishing.

Those letters were repurposed and some new letters were introduced. It was a messy match, and 1500 years of language evolution has only increased the distance between the sounds we make, and the letters we write.

As a result, English is alphabetic, but not phonetic. There is a simple sound letter match in only about 12% of words in English. How much of your literacy programming and budget do you want to allocate to that statistic?

2. Sounds are free

The sounds and letters of the English language are the ultimate open access knowledge. Buying them in a packaged program is just a con.

If you weren’t shown the sound-letter relationships in your teaching degree, shame on your degree, but in any case you can Google them or find them in the preface of a good dictionary.

3. Knowing your sounds is not the same as reading

I know all my sounds in French. I even sound reasonably convincing – in an Inspector Clouseau kind of way – when I “read” French. But I have no comprehension, so I’m not really reading.

Children who are failing in literacy in upper primary and high school are not failing because they don’t know their sounds. They are failing because they can’t comprehend.

Observe their attempts to read, write and spell and one thing is very clear – they know their sounds, and they over rely on them. Give them a phonics program and you are giving them more of what isn’t working for them.

4. Politicians are not educators

The push for phonics in England and Australia was spearheaded very conspicuously, almost personally, by the respective former Education Ministers Gove and Pyne. Politicians may have many skills… but they are not educators, and they are not educational researchers.

Educational reforms should not be shaped by personal predilections or political agendas.

5. Programs get it wrong

The narrow focus on sounds and letter patterns in phonics programs obscures more useful information for learning to read, write and spell. On occasion the material presented is just plain wrong.

A popular phonics workbook offers the following explanation for the word “technician”.

“Technician is a technical word. Although it is pronounced ‘shun’ at the end, it belongs to the word family ending in ‘cian’”

Teaching “cian” as a word family is linguistically inaccurate, and fails to teach how the word “technician” actually works.

“ian” is the suffix we attach to base words ending in “ic”, to turn them into the person who does the base word. So “technic” becomes “technician”, “magic” becomes “magician”, “electric” becomes “electrician” etc.

This knowledge develops spelling, builds vocabulary and increases reading comprehension. Being told that “cian” makes the “shun” sound does none of this.

6. Colouring-in is not literacy

Sticking balls of crepe paper on the letter “j” is not a good use of literacy learning time. Neither is colouring in all the pictures on the worksheet that start with “b”, particularly if you thought that picture of the beads was a necklace. And is that a jar or a bottle?

Busy work does not teach children to read and write.

7. There are no easy routes to literacy

Learning to read, write and spell is complex. The brain is not hardwired for literacy in the way it is hardwired for speech.

Each individual brain has to learn to read and write, and because our brains, our genes and our environments are all different, the pathways to literacy that our brains construct will be different.

If a single program could respond to this diversity then we would have solved the literacy problem a few hundred years ago when printed texts for the masses first took off.

Of course there are accounts of students whose progress was turned around by a phonics program – the comments section of this post will no doubt have some of those testimonials – but there are many more who languish in those programs.

Phonics programs can be helpful for students with very particular learning needs, but solutions to pointy end problems are not helpful for all learners.

The alternative?

Consider what the problem is that you are trying to solve before you commit to buying a phonics program.

If the problem is your students write phonetically, and cannot read phonically irregular words, then more phonics is not the solution.

If the problems are reading comprehension and quality of writing, then invest in your library and your staff. Buy quality literature and spend money on professional learning.

![]()

Misty Adoniou, Senior Lecturer in Language, Literacy and TESL, University of Canberra

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

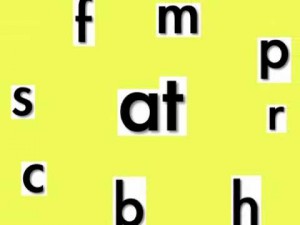

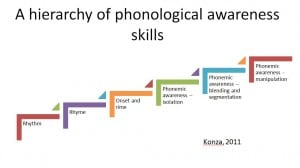

Phonics is understanding there is a relationship between the individual sounds (phonemes) of spoken language and the letters (graphemes) of written language. Once children understand that word can be broken up into a series of sounds, they need to learn the relationship between those sounds and letters – ‘the alphabetic code’ or the system that the English language uses to map sounds onto paper (Konza, 2011).

Phonics is understanding there is a relationship between the individual sounds (phonemes) of spoken language and the letters (graphemes) of written language. Once children understand that word can be broken up into a series of sounds, they need to learn the relationship between those sounds and letters – ‘the alphabetic code’ or the system that the English language uses to map sounds onto paper (Konza, 2011).  Sight words need to be taught explicitly and systematically, followed by regular practise in context.

Sight words need to be taught explicitly and systematically, followed by regular practise in context.

Rhyming words would be log, hog, bog. The word dog could then be separated into onset and rime (d – og) and then finally into all its phonemes (d – o – g). Without these experiences, children will have greater difficulty identifying the separate sounds in words and then translating the sounds into alphabetic script.

Rhyming words would be log, hog, bog. The word dog could then be separated into onset and rime (d – og) and then finally into all its phonemes (d – o – g). Without these experiences, children will have greater difficulty identifying the separate sounds in words and then translating the sounds into alphabetic script. The Big Six

The Big Six

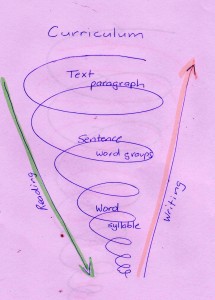

Through reading, the text is explored at a text and paragraph level, a sentence and word group level and a word and syllable level. Through writing, the cone then spirals back out from the syllable and word syllable level, to the word group and sentence level to the paragraph and text level connecting again to the big picture of the curriculum. I love the reciprocity between reading and writing as the two go hand-in-hand.

Through reading, the text is explored at a text and paragraph level, a sentence and word group level and a word and syllable level. Through writing, the cone then spirals back out from the syllable and word syllable level, to the word group and sentence level to the paragraph and text level connecting again to the big picture of the curriculum. I love the reciprocity between reading and writing as the two go hand-in-hand.

Preparations to read hook students into the text, build their field knowledge, allow them to follow the text when it is being read aloud and then assist students with decoding the text. I always construct one (visually or orally) prior to studying a text.

Preparations to read hook students into the text, build their field knowledge, allow them to follow the text when it is being read aloud and then assist students with decoding the text. I always construct one (visually or orally) prior to studying a text.

Fostering student talk is vital for learning, particularly when they employ the use of academic language. From their book, Content-Area Conversations,

Fostering student talk is vital for learning, particularly when they employ the use of academic language. From their book, Content-Area Conversations,  The last procedure is independent reading and of course it fits the last stage of the gradual release process (You do it alone). This is our goal – students independently reading and applying the reading strategies that they have been exposed to during the other procedures. Students choose their own texts but are encouraged to select from a wide variety of literary and informational texts (I have collected hundreds of books and refuse to part with any of them as they form a vital part of my classroom). Texts could include those previously read in the other reading procedures, other texts written by the same author and texts that match the students’ interests. It is all about reading for enjoyment.

The last procedure is independent reading and of course it fits the last stage of the gradual release process (You do it alone). This is our goal – students independently reading and applying the reading strategies that they have been exposed to during the other procedures. Students choose their own texts but are encouraged to select from a wide variety of literary and informational texts (I have collected hundreds of books and refuse to part with any of them as they form a vital part of my classroom). Texts could include those previously read in the other reading procedures, other texts written by the same author and texts that match the students’ interests. It is all about reading for enjoyment.

This is an opportunity to take photos and have students orally rehearse what they have been doing. This experience then forms the basis for a jointly constructed text.

This is an opportunity to take photos and have students orally rehearse what they have been doing. This experience then forms the basis for a jointly constructed text.

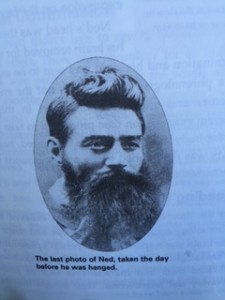

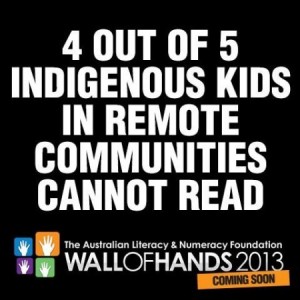

4 out of 5 indigenous kids in remote communities cannot read! Recently, Lyn Sharratt, the well-renowned co-author of Putting Faces on the Data, was working with a number of Metropolitan schools in Queensland and she used a photo she had taken of a bus shelter that displayed data similar to this statistic. Regardless of age or background, Lyn repeatedly expressed the sense of urgency needed around the teaching of reading.

4 out of 5 indigenous kids in remote communities cannot read! Recently, Lyn Sharratt, the well-renowned co-author of Putting Faces on the Data, was working with a number of Metropolitan schools in Queensland and she used a photo she had taken of a bus shelter that displayed data similar to this statistic. Regardless of age or background, Lyn repeatedly expressed the sense of urgency needed around the teaching of reading. I have begun my personal reading on this topic with the

I have begun my personal reading on this topic with the