Grand Conversation in Primary Classrooms

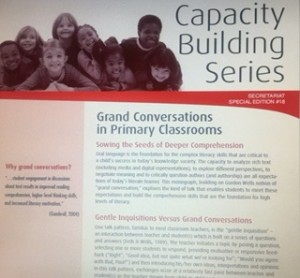

So much for my 30 posts in 30 days. Unfortunately, work commitments beat me this week and I am now about five posts behind my goal. My oral language workshop still prevails so tonight’s blog will look at Grand Conversations in Primary Classrooms, an article published as a part of the Capacity Building Series. This series was produced by the Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat to support leadership and instructional effectiveness in Ontario schools and the article I am referring to is 18th in the list.

I was introduced to the article when Lyn Sharratt (co-author of Putting Face on the Data) visited Metropolitan schools in February this year. Lyn chose an activity whereby each table group member was assigned a section to skim and scan in the article and then jigsawed to share the information gleaned.

Oral language is the foundation for the complex literacy skills that are critical to a child’s success in today’s knowledge society (Grand Conversations in Primary Classrooms, p.1) . The article begins by exploring the difference between gentle inquisitions (one talk pattern where the teacher is in charge and builds on a series of questions and answers) compared to Grand conversations (authentic, lively talk about text that has the potential to foster higher-level comprehension and student’s attitudes to reading). The talk pattern of a grand conversation is conversational where students and teachers exchange ideas, information and perspectives. The teacher is a member of the group, stepping in only when needed to facilitate and scaffold conversation.

This methodology works beautifully when you consider: who is doing the thinking? who is doing the talking?

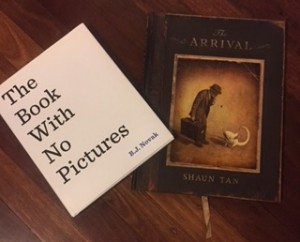

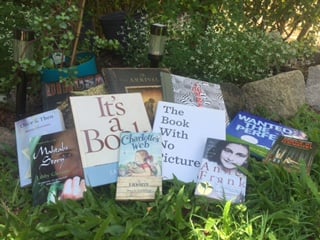

The critical first step is the choice of text – it needs to be stimulating and to support a grand conversation. It needs to be sufficiently challenging and multi-layered. For non-fiction, choose a text that presents content clearly and at times provides strong visual support. For a fiction text, choose books with interesting plots and characters, detailed descriptions and dialogue. Poetry and wordless picture books are also great choices.  The limited text of wordless picture books requires students to infer, make predictions and to express personal thoughts, feelings and opinions. The images must be visible to all participants.

The limited text of wordless picture books requires students to infer, make predictions and to express personal thoughts, feelings and opinions. The images must be visible to all participants.

Modelling conversational skills

Students need to taught how to consider the ideas presented in the text, how to share and defend their ideas and opinions and how to build on and question ideas of others. Initially, teachers may initiate conversations, ask big questions and model appropriate discussion skills. They will also need to be ready to step in and offer new questions or prompts when redirection is necessary. A teacher’s role will include assisting students to: accept different ideas and opinions; practise turn-taking and discussion techniques; and encourage the quieter students to have-a-go.

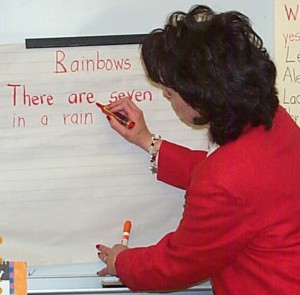

Teachers can model and students can practise these skills both in a whole class and small group situation. Anchor charts can be developed with students to record rules and norms for productive conversations.

The teachers’ role in a grand conversation shifts form discussion director to discussion facilitator to participant as students gain greater independence and proficiency (again this fits with the gradual release of responsibility).

The teachers’ role in a grand conversation shifts form discussion director to discussion facilitator to participant as students gain greater independence and proficiency (again this fits with the gradual release of responsibility).

Examples of Authentic Questions

• What do you think the author wants us to think?

• How would the story be different if another character was telling it?

• How does the author show his point of view? Do you agree?

• What do you think was the most important thing that happened?

• What was something that confused you or that you wondered about?

• How did you feel about what happened in the story? What made you feel that way?

• Are you like any of the characters?

In what ways?

• Did you agree with what (character’s name) did? Why?

• What do you think will happen next?

What do you think (character’s name) will do? What would you do in the same situation?

• Is there someone in the book you’d like to talk to? What would you say? What makes you want to say that?

Preparing Students for Discussion

The paper lists and describes a number of engaging and innovative strategies to support student thinking about the text prior to classroom discussion. These include:

- Literature logs and journals – students can record personal ideas, reactions, questions, connections and learning from their reading – provides sudents with the opportunity to reflect on and ‘ink their thinking’ (Donnelly, 2007) prior to discussion.

- Consensus board – after reading a rich text, each student draws a picture of what they think should be the focus of the discussion. Young students can label and older students can write a sentence or two. The pictures are grouped and labelled so that students can see what is considered most important and worthy of discussion (McGee and Para, 2009).

- Sketch-to-stretch – students use sketches to respond to a text being read to, with or by them (either at key points or at the end). Rather than a drawing, they use images, words, shapes and other symbols and then share their sketches in small groups as conversation starters (Whitin, 1996).

- Close reading of a text passage – students are invited to assist in selecting an important part of the story and then read, reread and discuss the passage in a small group to work out author’s stated and implied messages.

- Traffic lights – a good strategy for independent readers. Students are provided with three colours of post-it notes: green for parts of the text they agree with, think are important or make a connection with; red for parts they disagree with, did not like, make them upset etc; and yellow for parts they found confusing, left them wondering or raised questions.

Structuring Grand Conversations

Grand conversations have many names: literature circles, books clubs, reading response groups and literature discussion groups. Students come together to talk about text they have read or had read to them in order to answer to questions the text as they look at it from different points of view.

My apologies to the authors: the following lists are basically word for word of what is in their article:

Teacher read alouds

- Provides a context for rich conversations at all grade levels, especially when students are unable to read challenging and conceptually complex texts.

- Most commonly used as a whole-class activity.

- Frequently use picture books, both fiction and non-fiction,

- Bring students physically close to the text and hold it so that students can observe the pictures

- Students are encouraged to listen to the words and simultaneously examine the pictures in order to make sense of the text.

- Often the teacher interjects questions to assist students in clarifying understandings and constructing an overall understanding of the message conveyed by the text.

- After reading, teachers can use the read-aloud text to kick off a grand conversation.

- Students form a circle so that all speakers can see and hear one another.

- Teacher and students review collaboratively-established norms for group discussions.

- Teacher introduces a big question or prompt to initiate discussion and scaffolds the conversation as necessary.

Shared and guided reading groups

- Opportunity for students to practise student-led conversation about a text.

- After using a shared or guided approach to read a common text, the teacher presents a big question or prompt related to the text.

- Following review of the class anchor chart for grand conversations, the teacher withdraws, providing an opportunity for reading group members to engage in student-led conversation stemming from the question or prompt.

- Teacher checks in with other students and observes the functioning of the discussion group from a distance.

- After a few minutes, the teacher returns to the group and joins the conversation in progress.

- Students are encouraged to share, explain and elaborate their thinking about the question or prompt.

- Teacher may assist in resolving conflicts that may have arisen as a result of conflicting opinions or procedural issues such as turn-taking and conversation domination.

- Before ending the session, teacher and students reflect on and assess the functioning of the group in relation to the class guidelines for grand conversations.

Literature circles

-

Small groups of students (about three) can come together around a common theme or big idea using one or more texts.

-

Teacher selects books for these small-group discussions based on student needs and interests.

-

After listening to “book talks” given by the teacher, students may choose the text for their group discussion by holding a vote.

-

Before beginning the discussion teacher may want to introduce students to various conversational roles – such as discussion director, illustrator, word wizard and connector – as a way of scaffolding student-led conversations.

NB Goal is for students to participate in grand conversation without taking on a specific role.

Instructional conversations

- Whole-class or small-group discussions about a common text that combine instruction and conversation.

- Intended primarily to help students extract information from a text.

- Teacher begins with a specific curriculum goal in mind – a theme, topic or concept – and facilitates classroom conversation in order to meet that goal.

- Teacher and students share their prior knowledge and integrate it with new information gathered from the text to extend understanding of the topic or concept.

- Teacher facilitates sustained discussion encouraging students to share and clarify understandings, link new knowledge to prior knowledge and consider issues presented in the text from various points of view

- Teacher brings closure to the conversation by summarizing, drawing conclusions or establishing goals for the next conversation.

Idea circles

-

Heterogeneous small groups that support discussion focused on learning about a concept.

-

Purpose is to have students build an understanding of a concept through the dialogic exchange of facts and information (Guthrie & McCann, 1996).

-

Goal is to ensure that each student leaves the group with a clearer, more thorough and more accurate understanding of the target concept.

-

Multiple concept-related texts, at varying levels of reading difficulty, are provided by the teacher.

-

Each student reads their selected text, either independently or with a partner, for the purpose of gathering information about the topic under discussion.

-

Students then bring their information to the circle where the information is shared, clarified, extended and debated in order to co-construct a deeper and more elaborate understanding of the concept.

In conclusion

Being able to think deeply, articulate reasoning and listen purposefully increases student engagement. Grand conversations allow students to be leaders in a collaborative process that promotes the discussion of text in a meaningful way. This supports higher-order thinking skills and increases student learning and achievement. Who is doing the thinking and who is doing the talking in your classroom?

As we move through the gradual release of responsibility, it should move from teacher to student!

This is an opportunity to take photos and have students orally rehearse what they have been doing. This experience then forms the basis for a jointly constructed text.

This is an opportunity to take photos and have students orally rehearse what they have been doing. This experience then forms the basis for a jointly constructed text.