I have just finished reading through a paper entitled Accountable Talk Sourcebook: for classroom conversation that works (Michaels, O’Connor & Williams Hall, 2013). Again, I was introduced to accountable talk in the Metropolitan sessions led by Lyn Sharratt in February this year.

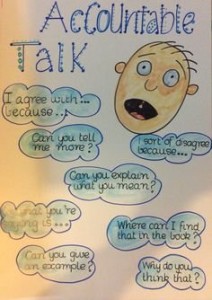

Anchor chart from https://tackk.com/fzmr3b

Talking with others about ideas and work is fundamental to learning. We need to be able to organise our thoughts coherently, hear how our thinking sounds out loud, listen to how other respond and hear others expand or add to our thinking.

Michaels, O’Connor and Williams Hall write that to promote learning, classroom talk must be accountable – to the learning community, to accurate and appropriate knowledge, and to rigorous thinking.

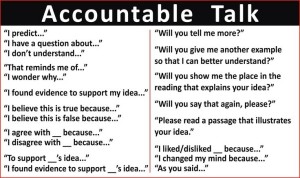

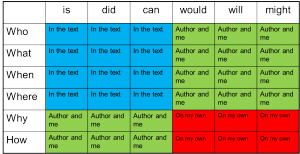

Shared as a part of Lyn Sharratt’s presentations to Metro schools

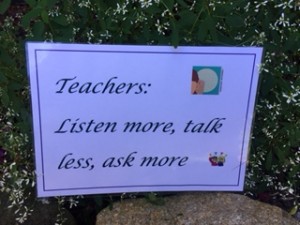

Accountable talk takes time and effort to implement. The teacher has to create norms and skills in the classroom by modelling discussion, questioning and probing and leading conversations. Then academically productive talk has to be co-constructed by the teacher and students. It is working towards a thinking curriculum. Setting up predictable, recurring routines that are well-practiced will assist students from different ethnic or cultural backgrounds as everybody will learn and share what is expected in the process of using accountable talk.

Conversations can be at a number of levels – whole class, small group, partner and peer or teacher conferences. All students have the right to engage in accountable talk and these discussions should occur across all year levels and in all learning areas.

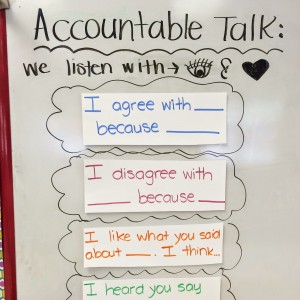

from Susan Jones (thank God it’s First Grade blog)

Accountability to the learning community

Students need to listen to one another and pay attention so they can use and build on another person’s ideas. The idea is to be able to paraphrase and expand on ideas, clarify when meaning is lost and to disagree respectfully. Both students and teachers will need patience, restraint and focused effort. In a classroom, there will be students actively talking together, participation in a variety of talk activities, attentive listening, respect, trust and risk-taking, challenges, and criticism and disagreement will be aimed at the idea, not the person.

Accountability to accurate knowledge

When students make a claim or observation, it needs to be as specific and as accurate as possible. In a classroom, students would make specific reference to previous findings to support arguments and assertions and unsupported claims would be questioned for further information, facts or knowledge. Students would be concerned with ensuring what they are saying is true and supportable.

Accountability to rigorous thinking

Claims and evidence would be linked together in a logical, coherent and rigorous manner. Evidence is examined critically. Different disciplines vary in the types of evidence. To support how a poem conveys emotions, the speaker may cite multiple pieces of textual evidence to support the interpretation. In history, the speaker may use historical facts to support a position that began as an opinion. In maths, the speaker will use a mathematically relevant basis to support their intuition. Attention will be paid to the quality of the claims – how well support? Is the evidence good? Is it sufficient? Authorative? Relevant? Unbiased?

How to set up accountable talk in the classroom

- Begin with a focus on academic purposes – this is critical. As a teacher, what are the academic goals for the lesson? What are the key concepts students need to learn? What are the big ideas they need to grapple with? How do the ideas linked to work already done?

Anchor chart from https://tackk.com/fzmr3b

- Ask what kind of instructional talk will support the accomplishment of those purposes – it needs to provided points of entry and opportunities for engagement for all student

- Plan – there needs to be a clear introduction of the task, time for student activity and a clear recap of the point, the big ideas that have been discussed and the new understandings that have been arrived at

- Consider the best class format to facilitate these academic goals – whole group, small group or partner work? Should the topic be set up and then stopped at a certain point for a partner discussion?

NB Recurring, familiar events and activities that take place at a certain time, in consistent ways and for consistent purposes will ensure that all students know how to participate in the conversation.

My thoughts

There is a lot of information around accountable talk on the internet. The link below has a video that captures the essence of students using accountable talk. It also has the anchor chart and featured image that I have used for this blog page.

Accountable talk will require lots of modelling and a slow, co-construction of sentence starters and guidelines. It links beautifully with many pedagogies and frameworks already being used in schools, such as Philosophy or yarning circles.

I also love how accountable talk can be used for any year level and in any learning area. Imagine the power of conversation that students can participate in if accountable talk has been fostered from the early years of schooling.

I love the phrase – a thinking curriculum. Accountable talk uses a gradual release model and builds to students doing the thinking and the talking…..about the curriculum with which they are learning.

Thanks to Cheryl for sharing this with me.

The limited text of wordless picture books requires students to infer, make predictions and to express personal thoughts, feelings and opinions. The images must be visible to all participants.

The limited text of wordless picture books requires students to infer, make predictions and to express personal thoughts, feelings and opinions. The images must be visible to all participants. The teachers’ role in a grand conversation shifts form discussion director to discussion facilitator to participant as students gain greater independence and proficiency (again this fits with the gradual release of responsibility).

The teachers’ role in a grand conversation shifts form discussion director to discussion facilitator to participant as students gain greater independence and proficiency (again this fits with the gradual release of responsibility).

Teacher think aloud: “As I read the text, I picture what is happening here. I think about the text more deeply, generate (make up) questions, and formulate (work out) answers to my questions.”

Teacher think aloud: “As I read the text, I picture what is happening here. I think about the text more deeply, generate (make up) questions, and formulate (work out) answers to my questions.”

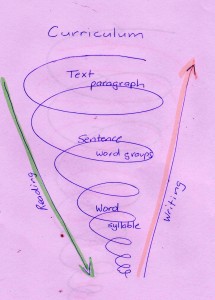

Through reading, the text is explored at a text and paragraph level, a sentence and word group level and a word and syllable level. Through writing, the cone then spirals back out from the syllable and word syllable level, to the word group and sentence level to the paragraph and text level connecting again to the big picture of the curriculum. I love the reciprocity between reading and writing as the two go hand-in-hand.

Through reading, the text is explored at a text and paragraph level, a sentence and word group level and a word and syllable level. Through writing, the cone then spirals back out from the syllable and word syllable level, to the word group and sentence level to the paragraph and text level connecting again to the big picture of the curriculum. I love the reciprocity between reading and writing as the two go hand-in-hand.

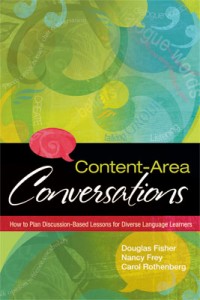

Fostering student talk is vital for learning, particularly when they employ the use of academic language. From their book, Content-Area Conversations,

Fostering student talk is vital for learning, particularly when they employ the use of academic language. From their book, Content-Area Conversations,  The last procedure is independent reading and of course it fits the last stage of the gradual release process (You do it alone). This is our goal – students independently reading and applying the reading strategies that they have been exposed to during the other procedures. Students choose their own texts but are encouraged to select from a wide variety of literary and informational texts (I have collected hundreds of books and refuse to part with any of them as they form a vital part of my classroom). Texts could include those previously read in the other reading procedures, other texts written by the same author and texts that match the students’ interests. It is all about reading for enjoyment.

The last procedure is independent reading and of course it fits the last stage of the gradual release process (You do it alone). This is our goal – students independently reading and applying the reading strategies that they have been exposed to during the other procedures. Students choose their own texts but are encouraged to select from a wide variety of literary and informational texts (I have collected hundreds of books and refuse to part with any of them as they form a vital part of my classroom). Texts could include those previously read in the other reading procedures, other texts written by the same author and texts that match the students’ interests. It is all about reading for enjoyment.

This is an opportunity to take photos and have students orally rehearse what they have been doing. This experience then forms the basis for a jointly constructed text.

This is an opportunity to take photos and have students orally rehearse what they have been doing. This experience then forms the basis for a jointly constructed text.

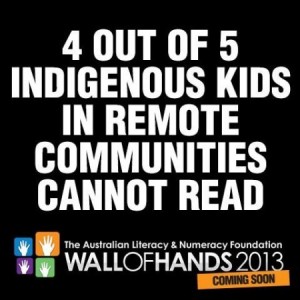

4 out of 5 indigenous kids in remote communities cannot read! Recently, Lyn Sharratt, the well-renowned co-author of Putting Faces on the Data, was working with a number of Metropolitan schools in Queensland and she used a photo she had taken of a bus shelter that displayed data similar to this statistic. Regardless of age or background, Lyn repeatedly expressed the sense of urgency needed around the teaching of reading.

4 out of 5 indigenous kids in remote communities cannot read! Recently, Lyn Sharratt, the well-renowned co-author of Putting Faces on the Data, was working with a number of Metropolitan schools in Queensland and she used a photo she had taken of a bus shelter that displayed data similar to this statistic. Regardless of age or background, Lyn repeatedly expressed the sense of urgency needed around the teaching of reading. I have begun my personal reading on this topic with the

I have begun my personal reading on this topic with the