Understanding the Reading Process – The Big Six

The final component of Konza’s Big Six and the goal of reading is comprehension. Each of the first five components of the Big Six contributes to comprehension. This is a summary of Konza’s original paper and the supporting paper on comprehension.

Comprehension

Comprehension is not just finding answers in a piece of text – it is an active process whereby the reader creates a version of the text in his or her mind (Konza, 2011).

Comprehension is not just finding answers in a piece of text – it is an active process whereby the reader creates a version of the text in his or her mind (Konza, 2011).

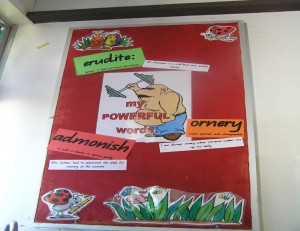

To comprehend text, students not only need to be able to decode but to also understand: vocabulary; background knowledge; the semantic and syntactic structures to help predict relationships between words; and verbal reasoning. Comprehension requires engagement with the text at a deep level.

Researchers have identified a number of behaviours and strategies that good readers use to gain meaning from text. The following are four important behaviours that characterise good readers and these are expanded upon in Konza’s supporting paper on comprehension.

Briefly, good readers:

- Understand the purpose of their reading– they know why they are reading and how to accomplish the task eg when to skim, when to scan or when to read closely.

- Understand the purpose of the text – they are aware of how the author’s purpose is reflected in the a text and the particular characteristics of different text types.

- Monitor their comprehension – they can integrate what they are reading with what they already know; focus on relevant parts of the text; distinguish between major content and supporting detail; monitor predictions; and evaluate content.

- Adjust their reading strategies – they know when to go back and reread; when to slow reading rate; and when to use chunking and decoding strategies with their vocabulary knowledge.

Levels of text comprehension

Independent level: reader can read most of text fluently (no more than 1 in 20 words difficult – success rate of at least 95%). To gain meaning from the text, students need to be able to read it fluently.

Instructional level: reader finds text challenging but manageable – can read with support (1 word in10 is difficult or unknown – success rate of 90%). Must have support.

Frustration level: reader has difficulty with more than 1 word in 10 – success rate less than 90%. Constant interruption results in frustration. Reading the text aloud exposes them to more sophisticated language structures and vocabulary – teacher can also do think alouds.

Guidelines and strategies

- Comprehension needs to be taught, not just tested – strategies need to be taught and explained along with guided practice.

- A variety of reading materials should be used, including short text – text types of all lengths can be used with short ones being particularly useful for struggling readers.

- Active listening should be taught – oral comprehension precedes reading comprehension but requires active listening. Give students tasks such as listening for specific information and teaching them strategies to remember the information. Barrier games require active listening and can be adapted for any age group.

- Readers need multiple strategies – students need a range of active comprehension strategies (see below – elaborations from Year 4 Australian Curriculum English).

Specific strategies for developing comprehension

I will list Konza’s specific strategies and a couple of the ideas. For more detail, go to her supporting paper.

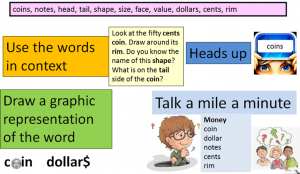

- Prepare students before reading – what do students already know, make predictions using title and illustrations, discuss other texts on similar topic, introduce new vocabulary.

- Facilitate engagement during reading aloud – read story/section with few interruptions – questions before and after reading more effective than during reading, emphasise new words that were introduced before reading, stop a few times for comments.

- Facilitate student comprehension during independent reading – teach students to use ‘fix-up’ strategies when meaning is lost, help them make connections.

- Promote comprehension after reading – identify key words, look for sequence and cause and effect, link to own experiences, retell story in different way – puppets, change the ending, change to another form, use graphic organisers, use glossaries, dictionary and thesaurus.

- Use questioning as a comprehension strategy – examples are Blank’s levels of questioning, Bloom’s taxonomy, 3H (Here, Hidden, In my Head).

Guidelines for classroom questioning

Konza also lists a number of guidelines for classroom questioning such as: phrasing questions clearly, using lower order questions and a brisk pace when checking understanding of basic factual material; using extended wait time for higher order questioning; asking questions before and after reading for older and higher ability students; and mainly asking questions after reading for younger students and those who are struggling.

Konza (2011) concludes by writing that comprehension enhances both the quality of our learning and the quality of our lives. Some children will acquire comprehension skills easily whereas others will require teachers to have a deep understanding of all the processes involved and how best to teach them.

My Addition

Australian Curriculum English

For readers in Australia – these are the comprehension strategies mentioned in English/Year 4/Literacy/Interpreting, analysing, evaluating

Use comprehension strategies to build literal and inferred meaning to expand content knowledge, integrating and linking ideas and analysing and evaluating texts (ACELY1692)

- making connections between the text and students’ own experience and other texts

- making connections between information in print and images

- building and using prior knowledge and vocabulary

- finding specific literal information

- asking and answering questions

- creating mental images

- finding the main idea of a text

- inferring meaning from the ways communication occurs in digital environments including the interplay between words, images, and sounds

- bringing subject and technical vocabulary and concept knowledge to new reading tasks, selecting and using

- texts for their pertinence to the task and the accuracy of their information

Australian Curriculum

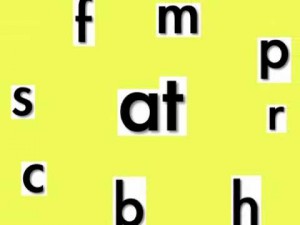

Phonics is understanding there is a relationship between the individual sounds (phonemes) of spoken language and the letters (graphemes) of written language. Once children understand that word can be broken up into a series of sounds, they need to learn the relationship between those sounds and letters – ‘the alphabetic code’ or the system that the English language uses to map sounds onto paper (Konza, 2011).

Phonics is understanding there is a relationship between the individual sounds (phonemes) of spoken language and the letters (graphemes) of written language. Once children understand that word can be broken up into a series of sounds, they need to learn the relationship between those sounds and letters – ‘the alphabetic code’ or the system that the English language uses to map sounds onto paper (Konza, 2011).  Sight words need to be taught explicitly and systematically, followed by regular practise in context.

Sight words need to be taught explicitly and systematically, followed by regular practise in context.

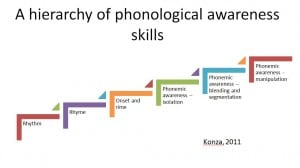

Rhyming words would be log, hog, bog. The word dog could then be separated into onset and rime (d – og) and then finally into all its phonemes (d – o – g). Without these experiences, children will have greater difficulty identifying the separate sounds in words and then translating the sounds into alphabetic script.

Rhyming words would be log, hog, bog. The word dog could then be separated into onset and rime (d – og) and then finally into all its phonemes (d – o – g). Without these experiences, children will have greater difficulty identifying the separate sounds in words and then translating the sounds into alphabetic script.