reblogged from Comfortspringsstation

My two youngest teenage children won’t like me telling you this, but at times, I still read aloud to them – albeit texts like Shakespeare’s The Tempest (difficult for most literate adults to read, let alone a 17 year old completely uninterested in navigating Shakespeare’s difficult language).

Although growing up, I had always been an avid reader, I credit Professor Kerry Mallan from Queensland University of Technology for expanding my limited repertoire of reading genres. As a part of a Children’s Literature subject in my post graduate degree, Professor Mallan read aloud in most lectures. One example was when she read expressively from a book about some rogue cats and then she stopped, leaving me wanting more. Unfortunately, I cannot remember the author of that particular text but I do remember going straight to a library the next day and borrowing it so I could finish the story.

There began my love for all genres, with fantasy and science-fiction now being two of my favourites. I also saw the power of reading aloud to students and stopping at points that left them gasping for more.

Never underestimate the power of reading to students.

As stated in my previous blog, the authors of First Steps in Reading (FSiR) recommend seven reading procedures. Two of these procedures fit quite nicely within the ‘I do’ step of the Gradual Release of Responsibility.

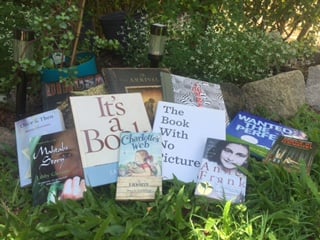

The first is Reading to students – this is reading for sheer, unadulterated pleasure. A wide variety of texts should be chosen, it should be uninterrupted and daily for about 10-15 minutes. Choose texts you enjoy and encourage students to bring in texts they enjoy. Activate their prior knowledge and demonstrate enjoyment, surprise, suspense and other reactions as you read. Disrupt the flow only if meaning has been lost, allow time for students to reflect on and respond to what has been read, and make texts available for students to explore later.

I remember my long-time teaching partner, Judy and I scheduling the reading aloud to students as a daily routine. It became a routine that students looked forward to and had them clamouring for more at the end of the 15 minutes.

Modelled reading, the second procedure, is where the focus is on ‘explicit planning and demonstration of selected reading behaviours’ (Reading Resource Book, p11). Teachers choose a text that allows multiple demonstrations and use clear ‘think aloud’ statements that have a single or limited focus. This behaviour is most effective when students are asked to ‘have-a-go’ at the behaviour as soon as possible after the demonstration. Sessions are most effective when they are kept to five to ten minutes.

Again the text is introduced to the students to activate prior knowledge. The teacher pauses at a pre-determined place to demonstrate the reading behaviour and this is continued throughout the reading of the text. Students can ask clarifying questions but the focus is on the teacher ‘think-alouds’. It is important to allow students to review the behaviour – a cumulative chart can be established to record the modelled behaviours.

Thinks of all those great texts that you genuinely love or are interested in and share those. Choose texts and reading behaviours that link to the curriculum you are teaching. In a world governed by technology, teachers have an opportunity to share a genuine love of reading and to ignite that passion in students.