The instructional goals of any lesson need to be a combination or balance of the three phases of learning – surface, deep and transfer. An expert teacher knows when and how to help students move from surface to deep and transfer learning. Despite whatever phase of learning the two key reminders are:

- Learning intentions and success criteria need to be clearly signalled.

- The instructional strategy with the highest importance is student learning.

Surface learning is the focus of Chapter 4 of Hattie, Fisher and Frey’s text Visible learning for mathematics.  When students are at the the surface phase of learning, high-impact approaches that foster initial conceptual understanding are followed by linked procedural skills. The tasks are efficient, often more engaging and designed to raise student motivation. When considering the fluency quadrant, many tasks will be of low difficulty and low to moderate complexity. There should be discussion and opportunities to connect the tasks to students’ learning and understanding.

When students are at the the surface phase of learning, high-impact approaches that foster initial conceptual understanding are followed by linked procedural skills. The tasks are efficient, often more engaging and designed to raise student motivation. When considering the fluency quadrant, many tasks will be of low difficulty and low to moderate complexity. There should be discussion and opportunities to connect the tasks to students’ learning and understanding.

…observing someone doing something uses many of the same neural pathways as when you perform the action yourself. (Hattie, Fisher and Frey, 2017, p107).

One of my favourite references. Number talks helping children build mental math and computation strategies by Sherry Parrish

Making number talks matter by Cathy Humphreys and Ruth Parker

This is why number talks, guiding questions, worked examples and direct instruction are so powerful. I am not going to go in-depth into these as the text does it beautifully. What I will say it that I was first introduced to number talks a couple of years ago when I was doing some work around the development of mental calculation. I became an immediate advocate and have bought a number of texts that illustrate how number talks are conducted.

I will also mention that direct instruction is especially useful in developing students’ surface-level learning but it has the following caveats. It should not:

- be used as the sole means of teaching mathematics.

- consume a significant part of the instructional time available for learning.

- always have to be used at the beginning of a lesson.

All four activities enable teachers to demonstrate the kinds of questioning and listening strategies that exemplify excellent mathematical practice as well as give their students opportunities to begin building these habits of mind (Hattie, Fisher and Frey, 2017, p119). Self-verbalisation and self-questioning, skills that help students think critically, have an effect size of 0.64. The text also provides some simple sentence frames that can be used to facilitate student metacognitive thinking (which has an effect size of 0.69).

In the last part of the chapter, the authors consider how to use vocabulary, manipulatives, spaced practice with feedback, and mnemonics strategically.

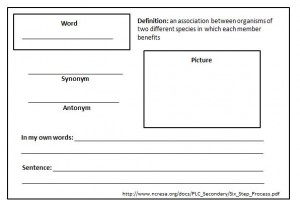

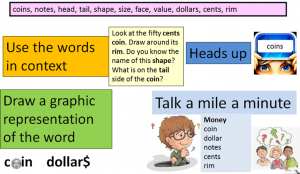

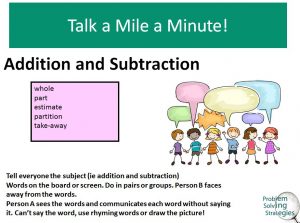

Vocabulary instruction is important in all the phases of learning but it is often in the surface phase that students begin to build academic language. Researchers such as Beck that as teachers, we need to support students in the appropriate terminology but not give away the mathematical challenge. A focus on vocabulary has always been a focus in the work my colleagues and I have done in mathematics and numeracy.  There are many vocabulary games that can be used in warm-up or transition times and we have always promoted the use of word walls and graphic organisers, the latter two being addressed in this chapter.

There are many vocabulary games that can be used in warm-up or transition times and we have always promoted the use of word walls and graphic organisers, the latter two being addressed in this chapter.

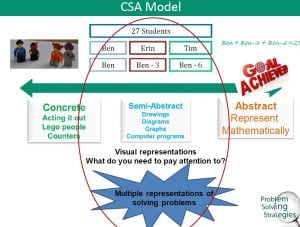

The CSA model used for problem solving strategies

Using manipulatives in all the learning phases helps build the links between the object, the symbol and the mathematical idea. It has an effect size of 0.5. Once again, my colleagues and I have promoted the use of manipulates and have commonly referred to the Concrete Semi-abstract Abstract (CSA) model.

Using the dual approach of spaced practice and feedback teaches students about the task and about their thinking. Spaced practice, giving multiple exposures to an idea over several days to attain learning and then spacing the practice of skills over a long period of time, has an effect size of 0.71. Feedback about the process (and not just the task) moves students into deeper learning and has the added advantage of giving a student agency so that they rely lesson on outside judgments and have a more positive mindset.

The use of mnemonics has an effect size of 0.45 and assist students to recall a substantial amount of information.

The authors give readers an insight into research based tasks that have a high effect size in the surface phase of learning. This strong start sets the stage for meaningful learning. Too often, however, the learning ends at the surface level. Teaching for deep and transfer learning must occur. My next blog will look at making learning visible in the deep learning phase.

Hattie, J., Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2017). Visible learning for mathematics What works best to optimize student learning Grades K-12. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

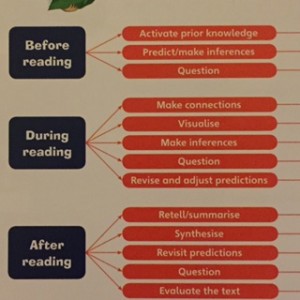

Comprehension is not just finding answers in a piece of text – it is an active process whereby the reader creates a version of the text in his or her mind (Konza, 2011).

Comprehension is not just finding answers in a piece of text – it is an active process whereby the reader creates a version of the text in his or her mind (Konza, 2011).